For Britain and her allies 1942 had been a year opening in disaster: it ended in victory. At least the tide had visibly turned, by 1943 the German Navy had suffered tragic losses, but the war was not yet over.

To support essential war industries with scarce raw materials, two German blockade-runners code-named Bernau (MS Osorno) and Trave (MS Alstrufer) sailed from Kobe, Japan on October 1943 for …occupied France.

Operation Bernau succeeded, Trave failed.

Before dawn on 27th December 1943 the Alstrufer was spotted by an RAF Sunderland Flying boat and later attacked and sunk by a Checkoslovak manned Liberator Bomber that evening.

Unaware of the Alstrufer’s interception and sinking a force of 11 German destroyers and motor torpedo boats set sail from the Gironde river to escort her through the most dangerous waters close to the French Coast. British 6 inch armed cruisers Glasgow and Enterprise who had sailed from the Devon Naval base to intercept the blockade runners, knew of the loss and also that an enemy covering force was at sea. They now proceeded to take up position between the German ships and their French bases.

At 12:45hrs on 28th December the cruisers made radar contact and one hour later visual sighting and the battle commenced.

In all 514 men died, and a further 300 were left in the water to die.

At first light on 29th December an Irish Merchant Vessel the Kerlouge left the port of Lisbon bound for Dublin with a cargo of oranges. At 9:45 that morning when she was in a position some 360 miles equidistant South of the Fasnet and West of Brew two Fock Wolf bombers circled the ship and morsed “SOS Lifeboats – Follow”. The captain of the Kerlogue Tom Donoghue responded by altering his course to a Southeasterly direction into the Bay of Biscay, which at that time was a ‘sink on site zone’.

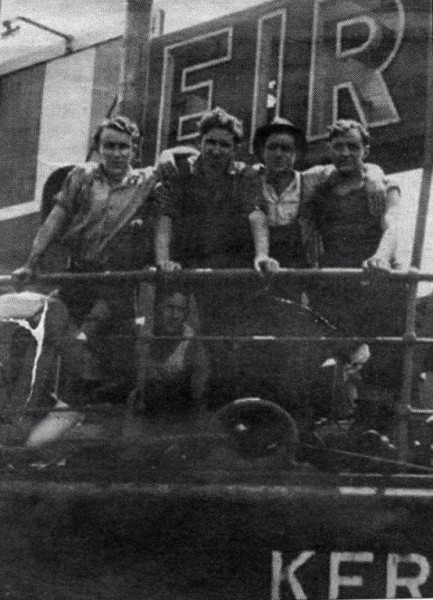

Two hours later at 11:45hrs the Kerlogue arrived in the Bay of Biscay where they came upon the aftermath of the previous day’s naval engagement. Immediately the Kerlogue set about rescuing as many survivors as they could. For ten hours the rescue operation continued. She took aboard 168 Germans. Because of the condition of the survivors and a shortage of supplies captain Donoghue decided to sail to Cork.

Two survivors, both very badly burned died on board. One that morning the other later that evening. They were buried at sea.

The following morning 31st December 1943 Lieutenant Engineer Adolf Braatz, who had also sustained sever burns died. It was decided that his body would be retained for burial in Ireland.

At 22:00hrs that evening the Kerlogue broke radio silence 30 miles South of Fasnet. Captain Donoghue called Valentia Radio giving this message:

“Kerlogue proceeding to Cobh. T. Dunoghue Master, expect arrive 2am. Have on board 164 survivors, 7 badly injured and 1 dead. Please instruct port control that I require medical assistance. Have no food, water or clothing. Kindly telegraph my owners circumstances. Telegraph “Steam” Waterford. On behalf of Master, Officers, Crew and survivors, we wish you a happy New Year. T. Donoghue, Master.” They replied “well done Kerlogue will see your message will get through.”

The Kerlogue eventually arrived in Cobh at 2:48hrs on January 1st 1944.

The worst of the cases were taken away by ambulance to Cork. Those who could move around on their own steam were provided with food and drink.

One of the survivors was so badly injured he was given up for dead, but a young trainee doctor insisted he was still alive and should be given emergency treatment. That German was Petty Officer Guntar Klar he survived. He underwent substantial plastic surgery.

Another seriously wounded Petty Officer, Helmut Weiss died from his burns and with Adolf Braatz were buried in the ‘Old Church Cemetery’ in Cobh. They were later re-interred in the German Cemetery in GlenCree in Co. Wicklow.

Today there are 26 of the 164 German survivors still living and 1 of the Kerlogue crew. See More